"Other countries are understanding because they have been ripping us for 50 years; they have been ripping us off right from the beginning.”

Stop me if you've heard this before, although I assume you have. The quote from President Donald Trump might be only a few hours old, but it's part of a decades-long view he's held on America's place at the center of the postwar boom in global trade.

In the president's telling the U.S. has selflessly, and naively, opened its markets to foreign competitors, which in turn have taken advantage of that generosity by undercutting American manufacturers with goods made with cheap labor and subsidized by tax breaks.

On the flip side, American companies are prevented from competing on a level playing field in international markets by a dastardly devised mix of tariffs, trade barriers, stealth taxes and tree-hugging environmentalists.

He narrowed his "ripping off" timeline to just 40 years in weekend interview with NBC News, but the theme has remained constant for much of the past month: April 2 will be "Liberation Day" and America will once again rule the global trading world.

There's only one problem.

It's already doing that.

The U.S. economy long ago realized that the real juice from the "consumption + investment + government spending" squeeze would come from services, not manufacturing.

And it has enjoyed unparalleled success since the global pandemic and left its international rivals, China included, wallowing in the dust.

Services, of course, generate a much wider profit margin than goods; think of Apple's (

AAPL) 46% gross margin in tech versus the 30.7% for ExxonMobil (

XOM) (the biggest U.S. exporter) in petroleum and the paltry 12.5% for General Motors (

GM) , the biggest U.S. automaker.

So while the U.S. has a trade deficit in goods, it's still earning more — a lot more, in fact — by selling services. U.S. companies generated $632 billion in overseas profits last year, 82% more than the $347 billion foreign companies earned in the U.S.

In a recent piece for Project Syndicate, Hausmann says that using U.S. stock valuations, "the value of US investments abroad can be estimated at $16.4 trillion," which are now suddenly a "far more attractive target for retaliation than tariffs on US exports."

They're also making more money with the same amount of people: European companies employed around 4.7 million people in the U.S. last year, while American companies were directly responsible for around 5 million jobs across the EU, the United Kingdom and Switzerland.

That certainly explains why the S&P 500 has shed some $5 trillion in value over the past month, amid the worst first-quarter performance for the benchmark in five years, as investors not only awaited details of Trump's April 2 tariff plans but also braced for the inevitable reprisals from the country's biggest trading partners.

Putting the immediate profits of America's biggest companies at risk in the hope that manufacturing jobs will somehow return over the next few years (or possibly longer) seems like a bad bet.

America doesn't need this trade war. It's already reaping massive rewards in terms of cheap goods, reliable foreign investment, lower government borrowing costs and growing corporate profits.

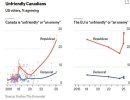

Are there unfair practices? Sure. India's protectionism needs a massive overhaul, China's intellectual property theft has gone unpunished for too long, and Europe's self-imposed role as the global tech policeman has become tiresome and, quite frankly, entirely too personal.

But those are all issues best solved in collective negotiations (the kind that Trump hates) rather than through unilateral sanctions (which he loves, as they present the chance to strike "deals" for which he can claim credit).

America won this trade war a long, long time ago. Revisiting the battlefield won't make anyone richer.

From the comments: Well hidden at the bottom of this argument is a nugget of truth: Manufacturing is not now, nor has it been for a good long time, a good creator of wealth. The days of '80,000 show up at the factory door each morning, they hand you a shovel, go home after 8 hours of simple but back breaking work churning out product' are long gone. Those kinds of jobs are what left the US, but did not take root in China (and Japan, and Korea, etc.). Those nations only got perhaps a quarter of that number of workers employed. (With that number further dropping as they made improvements in their processes.) If manufacturing does return to our shores, we will be lucky if 800 jobs ultimately return. That's not going to put a bunch of zing into employment numbers nor result in vast fat payrolls to be spent elsewhere.If the course of consumerism in America teaches us anything, it's that most people here already have vastly more 'stuff' than they actually 'need'. The biggest money long ago shifted from those who make 'stuff' to those that convince the average American to buy more 'stuff' (preferably on a short recurring schedule). For better or worse, that same dynamic is playing out all over the world.

These manufacturers are the same ones that took up lock, stock, and barrel to have their goods made in overseas countries because they did not want to pay Americans fair wages.

If things are so terrible, why are Apple, Google, Walmart, Amazon, Apple, Berkshire Hathaway, CVS Health, and United Healthcare - all American companies - among the top ten companies in the world in terms of revenue? The future is in AI, technology, medical equipment, chips (Nvidia).