Today, Speaker John Boehner stated that his party’s leverage comes from the fact that it retained control of the House. Yet they lost the popular vote. How can this be?

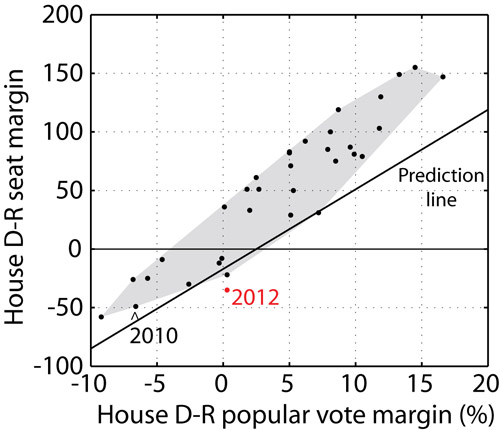

Before the election, I predicted that even if more people voted for Democratic House candidates, Republicans could still retain control. The reason I gave was redistricting since 2010, which has tilted the playing field significantly. The prediction was correct – though if anything, I underestimated the effect.

I estimated that Democrats would have to win the national popular vote by 2.5% in order to have a 50-50 chance of gaining control. I also predicted that the House popular vote margin would be D+0.0%, for Democratic gains of 2-22 seats . As of now, counting the leader in each undecided race, the new House will be 235 R, 200 D, a gain of only 7 seats. ThinkProgress reports a popular-vote tally of 50.3% D to 49.7%, a margin of D+0.6%. Both results are within range of my prediction.

However, this is quite notable. The popular vote was a swing of more than 6% from the 2010 election, which was 53.5% R, 46.5% D. Yet the composition of the House hardly changed – and the party that got more votes is not in control. This discrepancy between popular votes and seat counts is the largest since 1950.

Did I underestimate the tilt of the playing field? Based on how far the red data point is from the black prediction line, the “structural unfairness” may be higher – as much as 5% of the popular vote. That is incredible. Clearly nonpartisan redistricting reform would be in our democracy’s best interests.

Incidentally, some readers have suggested to me a reform in the Electoral College so that each Congressional district votes for its elector directly. As you can see, such a rule change would allow redistricting to influence the fairness of the Electoral College. Winner-take-all state races occasionally cause a problem, but which party gains is somewhat variable. It seems that there are worse things than the status quo.